How do you use symmetry-adapted linear combinations to explain water's molecular bonding?

1 Answer

An interesting use of the wave function (found in the context of the Schrodinger equation) is for symmetry-adapted linear combinations. Just a heads-up that this is a difficult topic, so don't feel bad if it seems confusing.

WAVE FUNCTIONS CAN HELP YOU PREDICT ORBITAL INTERACTIONS

The idea is, if two orbitals transform under different symmetries, they cannot merge to form molecular orbitals, regardless of whether they have similar energies or not.

Let's say we looked at the water molecule. Drawing it out on xyz coordinate axes, we get:

Now, there's something called a point group that every molecule belongs to, which can describe the ways the atomic orbitals of the central atom of choice and the group orbitals of the other atoms respond to symmetry operations.

When we draw symmetry elements (like axes and planes) onto water, we get that:

- It can do nothing, and achieve itself, indicating the identity operation

hatE . Simple enough. - It can rotate around the z-axis

180^@ before it becomes indistinguishable from the previous orientation. We call that the proper rotation operationhatC_2 around theC_2 axis because it takes two180^@ rotations to go around360^@ and achieve the identical molecule back. - It can be reflected over the xz-plane to give itself, which follows the vertical reflection plane operation

hatsigma_v(xz) . - It can be reflected over the yz-plane to give itself, which follows the vertical reflection plane operation

hatsigma_v(yz) .

It has no other symmetry elements. Since it has no

Overall that means it is a

http://www.webqc.org/symmetrypointgroup-c2v.html

The key aspects we are going to take from this are:

A_1, A_2, B_1, B_2 are the "irreducible representations" for each symmetry operation, which describe how the wave function changes upon the symmetry operation (rotate, flip, etc).1 means the wave function being operated upon did not change sign.-1 means it did.

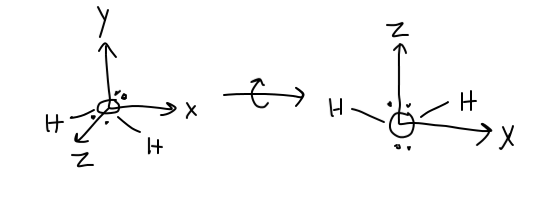

SYMMETRY OF OXYGEN'S VALENCE ORBITALS

If we examine oxygen's valence orbitals, we get that it has a

The wave function

These operations all return

If you look carefully, you may notice that the resultant orbital transformations correspond to the numbers in the character table above, which is how I decided what each orbital corresponds to.

I glossed over the

SYMMETRY OF HYDROGENS' GROUP ORBITALS

Now we move on to hydrogen. Here's where things get really tricky, so ask questions if you need to.

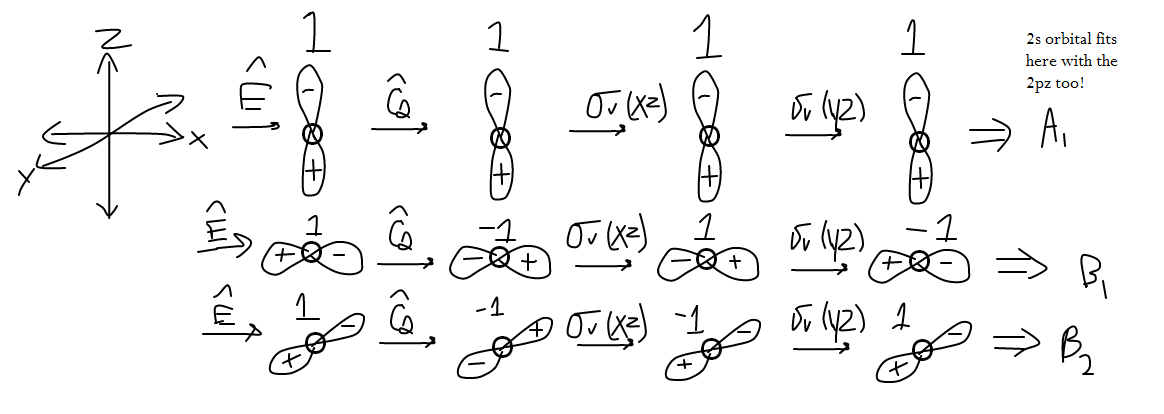

Let us choose the left hydrogen as our basis of transformation. Since there are two hydrogens and not one, we have to start with a reducible representation, and reduce it to the irreducible representation. Kind of a hassle, but nevertheless, we have to do it.

The operations give us:

- The

hatE leaves the1s orbitals alone, and there are two in the basis, so this returns1 per orbital, giving\mathbf(2) .H_a -> H_a , andH_b -> H_b . - The

hatC_2 operation switches the coordinates of the two1s orbitals, returning\mathbf(0) .H_a -> H_b , andH_b -> H_a . - The

hatsigma_v(xz) operation reflects the two1s orbitals, giving back the same orbitals with the same lobe sign (whichever signs they happen to be), and there are two orbitals, so this returns\mathbf(2) .H_a -> H_a , andH_b -> H_b . - The

hatsigma_v(yz) operation reflects the two1s orbitals in such a way that they swap coordinates with each other, so they end up returning\mathbf(0) .H_a -> H_b , andH_b -> H_a .

Therefore, our reducible representation is:

color(green)(Gamma = "2 0 2 0")

Reducing it takes some tricks with character tables that I don't want to go too much into, but the calculations turn out to be:

color(blue)(Gamma_(A_1)) = 1/(1+1+1+1)*[1*2*1 + 1*0*1 + 1*2*1 + 1*0*1] = color(blue)(1)

color(blue)(Gamma_(A_2)) = 1/(1+1+1+1)*[1*2*1 + 1*0*1 + 1*2*-1 + 1*0*-1] = color(blue)(0)

color(blue)(Gamma_(B_1)) = 1/(1+1+1+1)*[1*2*1 + 1*0*-1 + 1*2*1 + 1*0*-1] = color(blue)(1)

color(blue)(Gamma_(B_2)) = 1/(1+1+1+1)*[1*2*1 + 1*0*-1 + 1*2*-1 + 1*0*1] = color(blue)(0) We can write that as the IRREP

\mathbf(A_1 + B_1) .

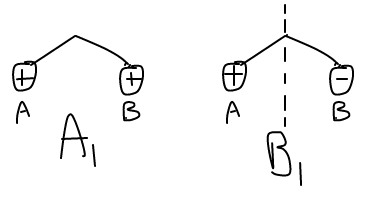

For these

The in-phase ones are

INTERACTION OF HYDROGEN'S GROUP ORBITALS WITH OXYGEN'S ATOMIC ORBITALS

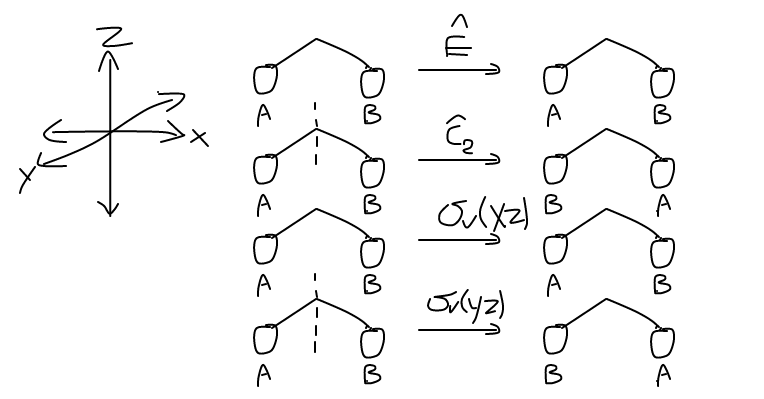

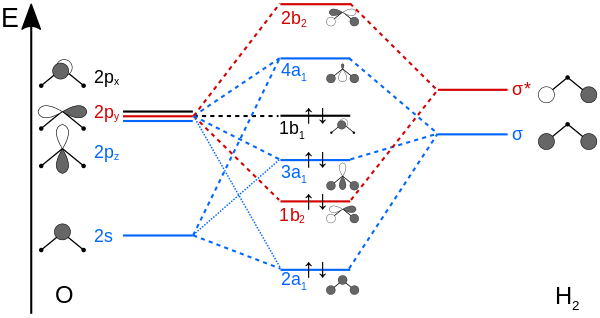

Ultimately, we have determined the symmetries for each orbital:

- Oxygen's atomic orbitals correspond as

[2s, 2p_z] harr A_1 ,2p_x harr B_1 , and2p_y harr B_2 . - Hydrogen's group orbitals correspond as

2s harr A_1, B_1

Since only orbitals of the same symmetry can overlap, hydrogen can only overlap its

It just so happens that the

So, we should expect it to yield a nonbonding molecular orbital (

https://upload.wikimedia.org/

https://upload.wikimedia.org/

(in the diagram, the coordinates axes are different; switch

x withy and you'll have it.)

When the

The nonbonding