Why is the electron configuration of chromium 1s^2 2s^2 2p^6 3s^2 3p^6 3d^color(red)(5) 4s^color(red)(1)1s22s22p63s23p63d54s1 instead of 1s^2 2s^2 2p^6 3s^2 3p^6 3d^color(red)(4) 4s^color(red)(2)1s22s22p63s23p63d44s2?

1 Answer

It's a combination of factors:

- Less electrons paired in the same orbital

- More electrons with parallel spins in separate orbitals

- Pertinent valence orbitals NOT close enough in energy for electron pairing to be stabilized enough by large orbital size

DISCLAIMER: Long answer, but it's a complicated issue, so... :)

A lot of people want to say that it's because a "half-filled subshell" increases stability, which is a reason, but not necessarily the only reason. However, for chromium, it's the significant reason.

It's also worth mentioning that these reasons are after-the-fact; chromium doesn't know the reasons we come up with; the reasons just have to be, well, reasonable.

The reasons I can think of are:

- Minimization of coulombic repulsion energy

- Maximization of exchange energy

- Lack of significant reduction of pairing energy overall in comparison to an atom with larger occupied orbitals

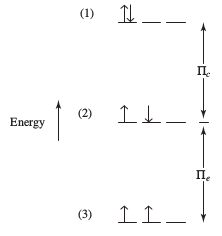

COULOMBIC REPULSION ENERGY

Coulombic repulsion energy is the increased energy due to opposite-spin electron pairing, in a context where there are only two electrons of nearly-degenerate energies.

So, for example...

ul(uarr darr) " " ul(color(white)(uarr darr)) " " ul(color(white)(uarr darr)) is higher in energy thanul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(darr color(white)(uarr)) " " ul(color(white)(uarr darr))

To make it easier on us, we can crudely "measure" the repulsion energy with the symbol

When you have something like this with parallel electron spins...

ul(uarr darr) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr))

It becomes important to incorporate the exchange energy.

EXCHANGE ENERGY

Exchange energy is the reduction in energy due to the number of parallel-spin electron pairs in different orbitals.

It's a quantum mechanical argument where the parallel-spin electrons can exchange with each other due to their indistinguishability (you can't tell for sure if it's electron 1 that's in orbital 1, or electron 2 that's in orbital 1, etc), reducing the energy of the configuration.

For example...

ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(color(white)(uarr darr)) is lower in energy thanul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(darr color(white)(uarr)) " " ul(color(white)(uarrdarr))

To make it easier for us, a crude way to "measure" exchange energy is to say that it's equal to

So for the first configuration above, it would be stabilized by

PAIRING ENERGY

Pairing energy is just the combination of both the repulsion and exchange energy. We call it

Pi = Pi_c + Pi_e

Inorganic Chemistry, Miessler et al.

Inorganic Chemistry, Miessler et al.

Basically, the pairing energy is:

- higher when repulsion energy is high (i.e. many electrons paired), meaning pairing is unfavorable

- lower when exchange energy is high (i.e. many electrons parallel and unpaired), meaning pairing is favorable

So, when it comes to putting it together for chromium... (

ul(uarr color(white)(darr))

ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr))

compared to

ul(uarr darr)

ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(uarr color(white)(darr)) " " ul(color(white)(uarr darr))

is more stable.

For simplicity, if we assume the

- The first configuration has

\mathbf(Pi = 10Pi_e) .

(Exchanges:

1harr2, 1harr3, 1harr4, 1harr5, 2harr3,

2harr4, 2harr5, 3harr4, 3harr5, 4harr5 )

- The second configuration has

\mathbf(Pi = Pi_c + 6Pi_e) .

(Exchanges:

1harr2, 1harr3, 1harr4, 2harr3, 2harr4, 3harr4 )

Technically, they are about

We could also say that since the

COMPLICATIONS DUE TO ORBITAL SIZE

Note that for example,

But, we should also recognize that

That is,

Pi_"W" < Pi_"Cr" .

Since a smaller pairing energy implies easier electron pairing, that is probably how it could be that

Indeed, the energy difference in